|

|

Construction of boundaries by Orthodox Jews called eruvim that allow certain activities on the Sabbath are unconstitutional, says UCLA Law Professor Alexandra Susman.

After reading many thousands of words of legal decisions that Orthodox Jews can affix “lechis” to utility poles and make them “doors,” thereby turning a public domain into a private one, we found a reasonable treatise on this subject by Susman.

Her 34-page detailed and scholarly work, written in 2009 for the University of Maryland Law Journal, is required reading for anyone who wants to voice an opinion on this subject. It sweeps away a vast swath of legal arguments that do not pass the test of common sense.

The 16,807-word analysis should be carried in full by the Southampton Press and posted on the paper's online version, 27east.com. If the paper won't do it, Jewish People Opposed to the Eruv should buy space for the article.

Susman, commenting on the most famous cases on this subject including decisions involving Tenafly, N.J. (2002) and Long Branch, N.J. (1987) says that courts have failed to develop “a thorough evaluation of an eruv in relation to the Establishment [of religion] Clause and the Free Exercise [of religion] Clause of the Constituton.

City councils and other local legislative bodies that make decisions about eruvim “lack a constitutional framework in which they can decide the issue,” she says.

|

The conclusion Susman reaches is that “A local government’s allowance of an eruv, which converts the public domain into the private domain and into the property of the Orthodox Jewish community, is a violation of the Establishment Clause of the Constitution.”

“It is not the role of American law to alleviate the internal burdens of Orthodox Judaism or any religion. It is the role of the courts and local governments to uphold the Constitution and safeguard all citizens’ rights to be free from religion,” she says in the treatise which can be copied and circulated by anyone in full text under the DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law.

Legal Decisions Defy Logic

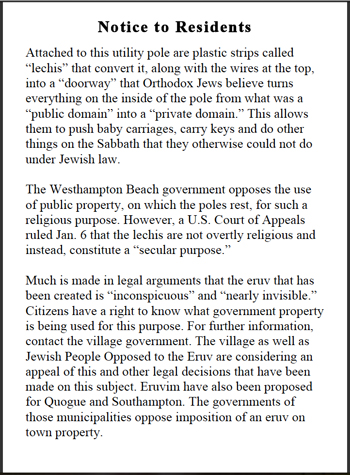

The Jan. 6 decision in the case involving Westhampton Beach, in which U.S. District judges note that the attached lechis are “nearly invisible” and that “no reasonable person who happens to notice them on utility poles would conclude that the government is “endorsing religion,” rests on the assumption that the community lacks knowledge of what is going on.

However, there has been extensive coverage of the dispute involving the East End Eruv Assn., WHB, Southampton & Quogue in the New York Times, Newsday, Southampton Press, Wall Street Journal, local WHB website, hamptons.com, The Jewish Week and other media and it shows no signs of abating especially since it’s now known that at least $4 million in donated and charged legal time is involved in the current dispute by both sides. Coverage is likely to increase, not subside.

Eruv Opponents Called “Bigots”

Nathan Diament of the Orthodox Union told the Jewish Week in 2002 that “The Tenafly eruv will stay up, religious bigotry has been defeated, and America is the better for it.”

The New York Post editorialized Jan. 9 that WHB and other places where eruvs have been challenged reflect not constitutional concerns but fear of an “influx of Orthodox Jews. The right word for that is bigotry. And as the court has just ruled, the Constitution offers no protection for these prejudices.”

Wikipedia has 328,000 entries under “eruv” and there are 11,900 on eruvin in Long Island.

The decisions of the U.S. Appeals Court in the WHB case and in Tenafly, N.J., appear less rational as publicity on this issue grows and the public is educated as to the nature of an eruv.

A basic position of the courts is that lechis don’t convey any religious message and are merely “non-sectarian.” But the meaning of the lechis to the observant is profound and conclusive. Without an eruv, the observant are not likely to settle in the area under question. It is a deal maker or breaker.

Legal decisions rest partly on the conclusion that the public does not know the meaning of those markers on the utility poles. This can be and is being overturned by publicity.

|

WHB, since there are no sign laws prohibiting this, could attach to all the poles with lechis an explanation of what lechis are and how they turn a “public domain” into a “private domain.”

The signs could give a partial explanation and then provide shortened tinyurls to provide full explanations of the eruvim.

Here is an explanation from chabad.org. The Jewish Press provides this background. There is no need for anyone to be ignorant about what an eruv is. Courts understand the religious meaning of the Crucifix, Star of David and star and crescent symbol of Islam but the eruv remains an obscure symbol to them, said a lawyer familiar with the case.

Lower Court Backed Eruv Opponents

Some courts have agreed with towns that eruvim violate the First Amendment. Judge William Bassler of the U.S. District Court sided with Tenafly in 2001 which wanted an eruv dismantled.

He ruled that “Since the Borough Council’s decision (by a 5-0 vote) was narrowly tailored to prohibit only the conduct that might generate the appearance of an entanglement between church and state, no constitutional infirmities resulted, and there is no cause for a court to second guess such a decision.”

A U.S. Appeals Court overturned the decision of Bassler and Tenafly had to pick up $300,000+ in attorney fees of the Tenafly Eruv Assn. as part of the settlement, according to Robert Sugerman of Weil, Gotshal & Manges, who is also representing EEEA pro bono in the actions vs. WHB, SH an Quogue.

Andrew Seidel, attorney for the Freedom From Religion Foundation, said in connection with the WHB case that “The religious significance of eruvin is unambiguous and indisputable” and it’s “absurd” for the Orthodox to “designate public and private property that they do not own as belonging to that sect.” Lechis have no meaning except as “a visual, public communication of a purely religious concept for religious believers of a single faith,” he said.

Weil Stresses “Largely Invisible” Markings

Weil, world’s 13th biggest law firm which has donated probably more than $1 million in legal time to EEEA since 2011, starts off the discussion of its work on its website with the words, “An eruv is a largely invisible unbroken demarcation of an area through which certain activities may be conducted outside the home on the Jewish Sabbath and Yom Kippur.”

It says EEEA contracted with utility companies [Verizon and PSEG/LIPA] “to attach the nearly invisible plastic strips that help create the eruv.” Headline on the entry is “Safeguarding the Free Exercise of Religion in New York.”

The 27east.com coverage of the Jan. 6 Appeals Court decision starts out by saying the Court upheld “the recent establishment of an invisible religious boundary encircling Westhampton Beach.”

Accepted is the alleged “invisibility” of the boundary. The lechis may be hard to see but they are not invisible. Also accepted, unwittingly, is the contention that the eruv is a “religious” boundary. That is the main issue in dispute. EEEA contends that the boundary allows “secular” activities such as pushing a baby carriage and carrying keys and is only religious in the sense that it is an "accommodation."

The Appeals Court, citing a decision involving an eruv in Long Branch, N.J., said “The city allowed the eruv to be created to enable observant Jews to engage in secular activities on the Sabbath. This action does not impose any religion on the other resident of Long Branch.”

WHB Mayor Maria Moore, by taking a low profile in the dispute, is aiding the EEEA in it quest to keep public discussion of the dispute to a minimum. The village has never conducted a public hearing on the issue. Two public hearings, attracting about 100 people each time, were conducted by Tenafly officials.

Neither she nor Sugarman, one of the two lead attorneys on the case, return “multiple request seeking comment” on the Appeals Court decision, said the 27east.com coverage by reporter Kyle Campbell. It's time for Mayor Moore to come out fighting against this legal assault on the town's properties. She should represent the will of WHB residents. There's no question that the vast majority of the residents oppose the religious use of public property.

Husch Blackwell Strategies has added FleishmanHillard alum Michael Slatin as a principal in its public affairs group.

Husch Blackwell Strategies has added FleishmanHillard alum Michael Slatin as a principal in its public affairs group. Rory Cooper, a veteran Republican operative and policy specialist, has joined Teneo’s Washington office as senior managing director in its strategy & communications practice.

Rory Cooper, a veteran Republican operative and policy specialist, has joined Teneo’s Washington office as senior managing director in its strategy & communications practice. Brian Fallon, who served as national press secretary for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential run, is signing on next month as Vice President’s Kamala Harris’ campaign communications director.

Brian Fallon, who served as national press secretary for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential run, is signing on next month as Vice President’s Kamala Harris’ campaign communications director. TikTok is nothing more than a Chinese propaganda tool that poses “a grave threat to America’s national security and, in particular, impressionable children and young adults,” say two Congressmen who want the platform registered as a foreign agent.

TikTok is nothing more than a Chinese propaganda tool that poses “a grave threat to America’s national security and, in particular, impressionable children and young adults,” say two Congressmen who want the platform registered as a foreign agent. Public Strategies Washington has added Abbie Sorrendino, a former aide to now Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer.

Public Strategies Washington has added Abbie Sorrendino, a former aide to now Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer.

Have a comment? Send it to

Have a comment? Send it to

No comments have been submitted for this story yet.