U.S. technology companies in March, along with civil rights leaders like the ACLU and Internet advocacy groups such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation, sent a letter to Congress demanding the federal government end ongoing mass surveillance efforts in the form of its “metadata” collection of telephone records.

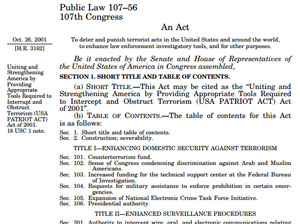

The letter specifically referred to Section 215 of the PATRIOT Act, a key provision of that law that gives the National Security Agency authority to collect data from virtually every phone call made in the United States. If not renewed, that provision --— which has been called unconstitutional and illegal by some policy experts — is set to expire June 1.

The letter specifically referred to Section 215 of the PATRIOT Act, a key provision of that law that gives the National Security Agency authority to collect data from virtually every phone call made in the United States. If not renewed, that provision --— which has been called unconstitutional and illegal by some policy experts — is set to expire June 1.

Government monitoring practices have become an issue of reform for several years now, a reaction to the public’s furor over the NSA’s massive surveillance initiatives brought to light by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden. Last year a bipartisan bill, the USA Freedom Act, was introduced in Congress. A Senate version of that bill would have halted the practice of metadata collection altogether; a watered-down version, passed in the House, shifted the onus of metadata collection to U.S. telephone companies. The bill ultimately died in the Senate in November.

Before that, in January 2014, President Obama proposed what the New York Times called “modest changes” to the NSA’s collection of metadata, suggesting intelligence agencies employ new search technologies in lieu of bulk collection, and, like the ill-fated House bill, suggested ceding that data gathering to the phone companies. Those new rules were finally unveiled this February. As it turns out, U.S. telephone companies are apparently leery about hoarding that content themselves, so intelligence agencies would still be in charge of collecting it until Congress decides otherwise, though there would be improved safeguards, such as purging irrelevant data after five years, and increased supervision into how it’s used. In other words, the practice of metadata collection is scheduled to continue pretty much just as before.

Americans are growing increasingly wary of government intrusion into their private communications. According to a March Pew Research Center poll, more than half — 52% — of U.S. adults described themselves as “very concerned” regarding government surveillance efforts, and 57% of those polled said they found such practices “unacceptable.” About 30% claimed they’re now taking measures to hide their personal information from federal surveillance programs, and 22% said they had changed their online communications behaviors in the wake of Edward Snowden’s 2013 bombshell NSA disclosure.

Oddly enough, several recent studies suggest all this data compiling might not be doing much good. In 2014, the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board issued a report that stated it was “aware of no instance in which the [metadata collection of telephone records] directly contributed to the discovery of a previously unknown terrorist plot or the disruption of a terrorist attack.” The New America Foundation, in a January 2014 study that analyzed hundreds of individuals recruited by terrorist groups since 9/11, found that “the contribution of NSA’s bulk surveillance programs to these cases was minimal …” and instead, “traditional investigative methods, such as the use of informants, tips from local communities, and targeted intelligence operations, provided the initial impetus for investigations in the majority of cases.” Finally, even the Obama Administration’s review board, in a December 2013 report titled “Liberty and Security In A Changing World,” admitted that “the information contributed to terrorist investigations by the use of section 215 telephony meta-data was not essential to preventing attacks.”

Perhaps what’s needed to assuage Americans’ personal privacy fears is a bottom-up approach. Last year, the European Court of Justice ruled in favor of its now famous “right to be forgotten” law, which mandates that, in some circumstances, individuals can force companies like Google to remove harmful or unwanted content about them from search results. Since that ruling, Google has allegedly received more than 200,000 such requests.

In the meantime, the New York Times in January detailed a National Academy of Sciences report that concluded there was currently no suitable technological alternative for the government’s retention of metadata, and that intelligence agencies should instead simply look to control how that amassed content is used. This development, coupled with recent terrorist attacks in Europe and Australia, make it unlikely a Republican-led Congress will let Section 215 of the PATRIOT Act expire anytime soon.

If you’re still waiting to make that phone call, it might be a while.

The techniques deployed by OJ Simpson's defense team in the 'trial of the century' served as a harbinger for those used by Donald Trump... People worry about the politicization of medical science just as much as they fret about another pandemic, according to Edelman Trust Barometer... Book bans aren't restricted to red states as deep blue Illinois, Connecticut and Maryland challenged at least 100 titles in 2023.

The techniques deployed by OJ Simpson's defense team in the 'trial of the century' served as a harbinger for those used by Donald Trump... People worry about the politicization of medical science just as much as they fret about another pandemic, according to Edelman Trust Barometer... Book bans aren't restricted to red states as deep blue Illinois, Connecticut and Maryland challenged at least 100 titles in 2023. The NBA, which promotes legalized gambling 24/7, seems more than hypocritical for banning player for placing bets... Diocese of Brooklyn promises to issue press release the next time one of its priests is charged with sexual abuse... Truth Social aspires to be one of Donald Trump's iconic American brands, just like Trump University or Trump Steaks or Trump Ice Cubes.

The NBA, which promotes legalized gambling 24/7, seems more than hypocritical for banning player for placing bets... Diocese of Brooklyn promises to issue press release the next time one of its priests is charged with sexual abuse... Truth Social aspires to be one of Donald Trump's iconic American brands, just like Trump University or Trump Steaks or Trump Ice Cubes. Publicis Groupe CEO Arthur Sadoun puts competition on notice... Macy's throws in the towel as it appoints two directors nominated by its unwanted suitor... The Profile in Wimpery Award goes to the Ford Presidential Foundation for stiffing American hero and former Wyoming Congresswoman Liz Cheney.

Publicis Groupe CEO Arthur Sadoun puts competition on notice... Macy's throws in the towel as it appoints two directors nominated by its unwanted suitor... The Profile in Wimpery Award goes to the Ford Presidential Foundation for stiffing American hero and former Wyoming Congresswoman Liz Cheney. JPMorgan Chase chief Jamie Dimon's "letter to shareholders" is a must-read for PR people and others interested in fixing America and living up to its potential... Get ready for the PPE shortage when the next pandemic hits... Nixing Netanyahu. Gaza carnage turns US opinion against Israel's prime minister.

JPMorgan Chase chief Jamie Dimon's "letter to shareholders" is a must-read for PR people and others interested in fixing America and living up to its potential... Get ready for the PPE shortage when the next pandemic hits... Nixing Netanyahu. Gaza carnage turns US opinion against Israel's prime minister. Trump Media & Technology Group sees Elon Musk's X as an option for those who want the free expression promised by Truth Social but without Donald Trump, owner of 57.3 percent of TMTG... Chalk one up for "anti-woke warrior" governor Greg Abbott as University of Texas lays off 60 DEI-related staffers... Five percent of Americans see the US as its own worst enemy, according to Gallup.

Trump Media & Technology Group sees Elon Musk's X as an option for those who want the free expression promised by Truth Social but without Donald Trump, owner of 57.3 percent of TMTG... Chalk one up for "anti-woke warrior" governor Greg Abbott as University of Texas lays off 60 DEI-related staffers... Five percent of Americans see the US as its own worst enemy, according to Gallup.

Have a comment? Send it to

Have a comment? Send it to

No comments have been submitted for this story yet.