Misdirection. Surely that word, that art, is something we understand. It is eagerly put to use by politicians, by shoplifters and by erring husbands—or so I'm told.

As a professional magician, I use more than my share of it, in my working mode and—by a certain compulsion—in my personal life, too.

I've just used misdirection on you, my reader. You see, I am not a magician. I am a conjurer. Strictly speaking, a “magician” would really do magic: miracles, impossible feats, supernatural stuff.

|

|

A conjurer performs only what appear to be miracles, but are accomplished by trickery— largely mechanical or optical—by the use of very specially-designed pieces of equipment, or by simple misdirection.

Misdirection occurs when the spectator (we avoid those words “victim” or “sucker”) has his/her attention subtly drawn away from the actions—the “moves”—of the performer, and directed to some area other than where the reality is taking place.

Only minimal explosions, crashing cymbals, flashes of light or other blatant displays should accompany a well-designed bit of misdirection, or the subject of such a distraction might recognize having been bamboozled and we might thus fail in our deception.

Here’s a basic example: I pick up a coin in my right hand and transfer it over to my left hand, which then closes over it.

Now, in actuality, I have picked up that coin but have only appeared to transfer it to my left hand. I have done this by casually seizing it—keeping up a running conversation as a minor form of misdirection!— briefly pointing a finger of my right hand toward my now-closed left fist, perhaps even shifting my grasp on the not-present coin presumed to be there in my left fist, and lifting that empty fist to a better viewing position, even though there is—now—nothing there to view, though I must believe that there is, to keep the spectator deceived.

And, while I’m handling that coin, I’m always looking at where it’s supposed to be, not where it actually is, and yet I will also make eye contact with the spectator that I’m deceiving, just to keep control of his/her attention …

Other “wider angle” misdirection on stage can be brought about by bolder approaches. During his superb full-evening show, the late, great, Harry Blackstone Senior—who taught me my very first magic trick—used to load a noisy flock of ducks into a large box painted like a doll’s house, then in a loud voice shout offstage, “Bring me my revolver!”

This brought out a uniformed assistant bearing a tray with the demanded instrument. The apparently clumsy chap would stumble, the revolver would tumble to the stage and skid over to Mr. Blackstone, who would stop it with his foot, wag his finger at the assistant and scold him, while the percusionist delivered great drum rolls and cymbal accompaniment. Harry would pick up the gun, fire a shot at the box of ducks, and that box would fold out flat. The ducks were gone …!

That cacophony of drums covered the fact that those ducks—who’d actually been loaded into a large black bag inside the “doll’s house”—had at that instant been swiftly yanked through the open back of the little house and across the stage precisely as the bumbling assistant had covered the action. The audience had been misdirected (there’s that word!) and thereby quite well deceived …!

In what we call “close-up” magic, you can just as easily be hornswoggled, have no doubt of that. In many cases, much of what could give away the secrets takes place 14 to 20 inches away from your eyes, though others can often see it at a greater distance. The performer of wonder has thus much better control because attention is limited to a smaller “cone of vision.”

A hand casually but openly placed on a hip can hold—and conceal—a playing card. An object moved to a different position on a table can take the observer’s attention, or a handkerchief just unfolded might serve to block view of a needed change of intent—all possible elements of misdirection so subtle that Beelzebub himself might be blamed …

Two of my good friends are Penn & Teller, a duo who regularly confound their fans in the Las Vegas jungle, a place where whirring wheels-of-chance and confounding tumbling dice separate naïve folks from their moolah.

These two experienced professional jesters, as a part of their regular stage show, completely, definitively and clearly offer everyone an exposure of an absolute classic of the conjurers repertoire, one perpetuated in the famous Hieronymous Bosch painting, “The Conjuror.”

It’s known as the Cups & Balls trick. Despite P&T’s careful, open, flashy, performance on a well-lit transparent table and their running account of each of the sleights involved—as they take place!—their audience leaves the theater totally flummoxed, but hugely entertained.

Language, too, is a large part of the conjurors’ process of misdirection. Simple, direct, phrasing accompanied by gestures and facial expressions can add substantially to the required distraction.

Yes, the conjuring art is a complicated and demanding one, and second, there much more to misdirection than simply “seeing the moves.” They must be studied in context.

So, dear reader, cast a very wary eye—or perhaps two—on the next magician/conjurer that you see. Watch for the most innocent of glances, cute smiles, a hand waved just a bit too much or casually placed in a pocket.

Notice when you are asked bland questions, a joke is told to relax you, or a chair is uselessly re-positioned. Did the magus misdirect you …? You may never know, but I sincerely hope that you were entertained, that you enjoyed being deceived, and that you would look forward to yet another such performance.

And, oh yes, I almost forgot. This 1,000-word caveat just offered you was yet another form of misdirection.

Or did you not catch my cunning—and calculated—misspelling of “percussionist” …?

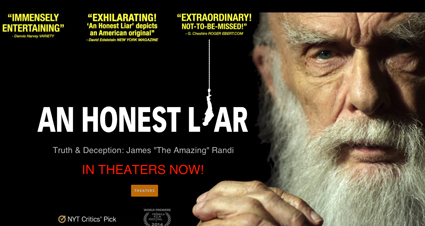

James Randi is a retired magician who performed with the stage name "The Amazing Randi." He now investigates paranormal phenomena and the history of magic.

Abandon traditional content plans focused on a linear buyer progression and instead embrace a consumer journey where no matter which direction they travel, they get what they need, stressed marketing pro Ashley Faus during O'Dwyer's webinar Apr. 2.

Abandon traditional content plans focused on a linear buyer progression and instead embrace a consumer journey where no matter which direction they travel, they get what they need, stressed marketing pro Ashley Faus during O'Dwyer's webinar Apr. 2. Freelance marketers and the companies that hire them are both satisfied with the current work arrangements they have and anticipate the volume of freelance opportunities to increase in the future, according to new data on the growing freelance marketing economy.

Freelance marketers and the companies that hire them are both satisfied with the current work arrangements they have and anticipate the volume of freelance opportunities to increase in the future, according to new data on the growing freelance marketing economy. Home Depot's new attempt to occupy two market positions at once will require careful positioning strategy and execution to make it work.

Home Depot's new attempt to occupy two market positions at once will require careful positioning strategy and execution to make it work. Verizon snags Peloton Interactive chief marketing officer Leslie Berland as its new CMO, effective Jan. 9. Berland succeeds Diego Scotti, who left Verizon earlier this year.

Verizon snags Peloton Interactive chief marketing officer Leslie Berland as its new CMO, effective Jan. 9. Berland succeeds Diego Scotti, who left Verizon earlier this year.  Norm de Greve, who has been CMO at CVS Health since 2015, is taking the top marketing job at General Motors, effective July 31.

Norm de Greve, who has been CMO at CVS Health since 2015, is taking the top marketing job at General Motors, effective July 31.

Have a comment? Send it to

Have a comment? Send it to

No comments have been submitted for this story yet.