People with an aversion to the news industry have more difficulty differentiating between actual news and “fake” news content, according to a recent report from the News Co/Lab at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication in collaboration with the University of Texas at Austin’s Center for Media Engagement.

The study, which sought to measure local communities’ news fluency as well as their attitudes toward the press, tested respondents’ ability to identify phony headlines and compared those findings along shared education, income and age characteristics. It discovered that those who harbor a dislike for the media are often bad at discerning fake news from the real thing, and worse, often don’t realize they’re doing so.

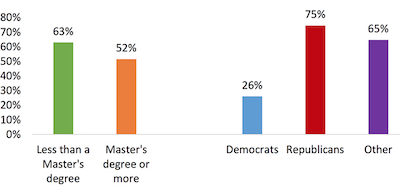

Respondents were asked for the first word that came to mind when they heard the word “news.” About 62 percent responded with a negative phrase, “fake, “lies,” "untrustworthy” or “BS” among the responses provided. The remaining 38 percent responded with a positive or neutral phrase such as “information” or “factual.” Those who used a negative word in reaction to the “news" identified as Republican 74 percent of the time, compared to 26 percent who identified as Democrat.

Percent Who Used a Negative Word in Reaction to "News." |

Participants were then shown a series of headlines or story ledes and were asked to identify whether that item was news, opinion, analysis or advertising content. Those who used a negative phrase to describe the news were less likely to distinguish news from opinion or advertising compared to those who used a positive or neutral phrase (73.8 percent vs. 79.5 percent, respectively).

The survey also discovered that education level seems to make a difference in someone’s ability to parse real news from phony content. Respondents were supplied with three headlines, two real and one fake. While the study found that most overall (62 percent) correctly identified which headline was fake, more than two-thirds (68 percent) of those with a college degree or more were able to successfully spot the fake headline, compared to 57 percent of those with less than a college degree.

Income also appeared to be a causal factor. Those earning $150,000 or more a year were statistically more likely to detect false news better than those making less than $30,000 a year (71 percent vs. 54 percent, respectively). The same goes for age: about two-thirds (66 percent) of respondents between the ages of 18 to 64 were able to correctly identify a fake news headline, compared to 56 percent of those ages 65 and older.

In another part of the survey, respondents were asked whether they occasionally require help finding the information they need online. Those who used negative phrases to describe the news were less likely to admit they ever needed help (34 percent) compared to those with positive or neutral reactions to the news (42 percent). Those with a high school education or less were also more likely (44 percent) to say they sometimes needed help finding information online compared to those with an associate's degree (38 percent) or those with at least a bachelor’s degree (34 percent).

Partisan identity, on the other hand, didn’t appear to be a clear causal factor in determining whether someone is more or less likely to be fooled by a fake headline (two communities polled revealed that Democrats were statistically more likely to spot fake news, but a third found that fewer than 60 percent overall were able to correctly identify a false headline, with no statistically significant differences in partisanship among this group). However, those identifying as Democrats were far less likely to use a negative word when describing the news compared to those identifying as Republicans (26 percent vs. 74 percent, respectively).

The News Co/Lab / Center for Media Engagement at UT Austin study surveyed more than 4,800 people in Macon, GA; Fresno, CA; and Kansas City, MO via Facebook between May and June.

A separate portion of the survey partnered with local newsrooms in those cities, surveying 88 journalists and 51 news sources via the Qualtrics research platform between July and October.

These findings also revealed a disparity between how reporters view themselves and the public’s perceptions of them. When asked if their news organization “is focused on helping the community,” 83 percent of journalists agreed, compared to only nine percent of the public. When asked if their newsroom “knows the community well,” 85 percent of journalists agreed, while only 29 percent of the public agreed with this statement. And while an overwhelming number of journalists (93 percent) felt their newsroom was “concerned with the community’s interests,” only 10 percent of the public agreed that this was true.

Trump Media & Technology Group today reported a $58.2M net loss on $4.1M in 2023 revenues, a disclosure that drove its stock price down 22.6 percent to $47.96.

Trump Media & Technology Group today reported a $58.2M net loss on $4.1M in 2023 revenues, a disclosure that drove its stock price down 22.6 percent to $47.96. Barry Pollack, an attorney at Wall Street’s Harris St. Laurent & Wechsler, has registered Julian Assange as a client with the Justice Dept. “out of an abundance of caution.”

Barry Pollack, an attorney at Wall Street’s Harris St. Laurent & Wechsler, has registered Julian Assange as a client with the Justice Dept. “out of an abundance of caution.” Paramount Global to slash 800 jobs in what chief executive Bob Bakish calls part of an effort to “return the company to earnings growth"... Rolling Stone editor-in-chief Noah Shachtman is exiting at the end of the month due to disagreements with chief executive Gus Wenner over the direction the magazine is taking... The New York Times broke the $1 billion barrier in annual revenue from digital subscriptions in 2023... Press Forward is investing more than $500 million to strengthen local newsrooms.

Paramount Global to slash 800 jobs in what chief executive Bob Bakish calls part of an effort to “return the company to earnings growth"... Rolling Stone editor-in-chief Noah Shachtman is exiting at the end of the month due to disagreements with chief executive Gus Wenner over the direction the magazine is taking... The New York Times broke the $1 billion barrier in annual revenue from digital subscriptions in 2023... Press Forward is investing more than $500 million to strengthen local newsrooms. The majority of news articles are read within the first three days of publication, according to a recent report.

The majority of news articles are read within the first three days of publication, according to a recent report. The Los Angeles Times gives pink slips to 115 people or 20 percent of its newsroom staff... TIME is also laying off about 30 employees, which is approximately 15 percent of its editorial staff... The Baltimore Banner, which was launched by Stewart Bainum in 2022 after he failed to buy the Baltimore Sun, added 500 subscribers per day in the three days following Sinclair Broadcast Group's deal to purchase the Sun.

The Los Angeles Times gives pink slips to 115 people or 20 percent of its newsroom staff... TIME is also laying off about 30 employees, which is approximately 15 percent of its editorial staff... The Baltimore Banner, which was launched by Stewart Bainum in 2022 after he failed to buy the Baltimore Sun, added 500 subscribers per day in the three days following Sinclair Broadcast Group's deal to purchase the Sun.

Have a comment? Send it to

Have a comment? Send it to

No comments have been submitted for this story yet.