|

| George C. Tagg, Jr. |

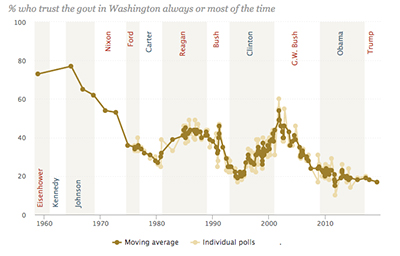

In these polarized times, the public is speaking with one voice on at least one subject: They do not trust government. In fact, trust in the government in Washington is at its lowest point since World War II. At the same time, access to information is at an all-time high, which offers governments an opportunity to close the gap between public expectations and political reality by improving the way they communicate.

This has nothing to do with what’s in the news cycle. This is a multi-generational trend. The lack of trust that the American public has in its government is shocking, even for those who regularly pay attention to the news. Trust peaked in Oct. 1964 when 77 percent of people told the Pew Research Center that they trusted their government in Washington. By the time Richard Nixon resigned in the Watergate scandal, that number had fallen to 36 percent. Trust fell even further during the Iran hostage crisis to 27 percent, and, while that seems low, it was still higher than at any point during the administrations of Barack Obama or Donald Trump. At no point since 2008 has trust in government been as high as it was during Vietnam, the Cuban missile crisis, the Iran Contra scandal, 9/11, or any other epochal event.

This leads me to believe that what has depressed trust in government has less to do with what has occurred since Obama got elected than in the information revolution that has dramatically increased the public’s interconnectedness over that same period. Obama campaigned with a MySpace page and a Blackberry device he had to give up when he was elected, notions that seemed revolutionary then but archaic now.

|

| PEW RESEARCH CENTER |

Part of the current challenge is that we’re only now discovering how the public is vulnerable to inaccurate information, which a recent MIT study found spreads faster on the internet than accurate information. People, it seems, are more likely than bots to spread false claims on the internet if it corresponds to their preconceived notions and “seems true.” This can become a major problem during public safety crises as we saw with the 2013 manhunt for the Boston Marathon bombers; false reports and conspiracy theories on Twitter were read by reporters on national television before authorities could debunk them.

Another problem for governments communicating with the public is in the affirmative. That is when government officials make easily preventable mistakes. An example of this was when a false alarm alerted the world that a ballistic missile was headed Hawaii’s way, a mistake compounded by the Governor not knowing his Twitter password which gave the world 15 minutes to contemplate the immediacy of nuclear war.

It is in these instances when government’s ability to quickly and clearly communicate is most important and when the public’s trust is most easily earned and most quickly lost. We see in the examples from Boston and Hawaii how the public will fill a communication vacuum whether by spreading misinformation in good faith or by imagining mushroom clouds. And though government performed its basic duty in both cases – they caught the Boston bombers, and there was no missile attack – they contributed to the overall lack of trust in government because of their incompetent communication.

This is fixable because the one thing that governments can count on is that there will be another crisis, perhaps something unavoidable due to a fire or flood, or maybe a manmade disaster like an unidentified serial killer. In either case, the public will turn to government for information that could be necessary to protect life and property. It is at this inevitable moment when the government faces a critical test that can either build or destroy trust.

There is an opportunity born of the certainty that this moment will arrive. What can be predicted can be prepared for. Governments need to prepare for crises as the norm. Otherwise, you’ll always be playing catch-up. I dealt with this first-hand while working at the Department of Defense and the State Department. Like many organizations, we often struggled to determine the best course for responding as we were juggling a live crisis. We can expect more crises to occur – that is a natural byproduct of the hyper-digital age we live in – but, if you have clear processes in place, the difficult patches are a lot easier to manage. Also, advance preparation frees up time to deliver essential services.

Of course, readying your crisis communications game plan is not the only way for government to rebuild trust with the public, but it is the quickest one. Knowing what to do in a crisis does not depend on political party, ideology, or any other factors than competence, foresight, focus, and experience. Also, it turns WiFi-enabled smartphones – currently, the tool of much of what is causing the problem – into a part of the solution.

Have a well-researched crisis plan in place. Because when an information mudslide hits, that truly is the difference between a good day and a disastrous day in the global news cycle.

***

George C. Tagg, Jr. is the Global Head of Government + Public Sector at Hill+Knowlton Strategies. He spearheads H+K’s work with cities, states and countries worldwide to provide strategic advice and messaging to the right audience regarding crisis management, trade promotion, e-governance and public advocacy campaigns.

The techniques deployed by OJ Simpson's defense team in the 'trial of the century' served as a harbinger for those used by Donald Trump... People worry about the politicization of medical science just as much as they fret about another pandemic, according to Edelman Trust Barometer... Book bans aren't restricted to red states as deep blue Illinois, Connecticut and Maryland challenged at least 100 titles in 2023.

The techniques deployed by OJ Simpson's defense team in the 'trial of the century' served as a harbinger for those used by Donald Trump... People worry about the politicization of medical science just as much as they fret about another pandemic, according to Edelman Trust Barometer... Book bans aren't restricted to red states as deep blue Illinois, Connecticut and Maryland challenged at least 100 titles in 2023. The NBA, which promotes legalized gambling 24/7, seems more than hypocritical for banning player for placing bets... Diocese of Brooklyn promises to issue press release the next time one of its priests is charged with sexual abuse... Truth Social aspires to be one of Donald Trump's iconic American brands, just like Trump University or Trump Steaks or Trump Ice Cubes.

The NBA, which promotes legalized gambling 24/7, seems more than hypocritical for banning player for placing bets... Diocese of Brooklyn promises to issue press release the next time one of its priests is charged with sexual abuse... Truth Social aspires to be one of Donald Trump's iconic American brands, just like Trump University or Trump Steaks or Trump Ice Cubes. Publicis Groupe CEO Arthur Sadoun puts competition on notice... Macy's throws in the towel as it appoints two directors nominated by its unwanted suitor... The Profile in Wimpery Award goes to the Ford Presidential Foundation for stiffing American hero and former Wyoming Congresswoman Liz Cheney.

Publicis Groupe CEO Arthur Sadoun puts competition on notice... Macy's throws in the towel as it appoints two directors nominated by its unwanted suitor... The Profile in Wimpery Award goes to the Ford Presidential Foundation for stiffing American hero and former Wyoming Congresswoman Liz Cheney. JPMorgan Chase chief Jamie Dimon's "letter to shareholders" is a must-read for PR people and others interested in fixing America and living up to its potential... Get ready for the PPE shortage when the next pandemic hits... Nixing Netanyahu. Gaza carnage turns US opinion against Israel's prime minister.

JPMorgan Chase chief Jamie Dimon's "letter to shareholders" is a must-read for PR people and others interested in fixing America and living up to its potential... Get ready for the PPE shortage when the next pandemic hits... Nixing Netanyahu. Gaza carnage turns US opinion against Israel's prime minister. Trump Media & Technology Group sees Elon Musk's X as an option for those who want the free expression promised by Truth Social but without Donald Trump, owner of 57.3 percent of TMTG... Chalk one up for "anti-woke warrior" governor Greg Abbott as University of Texas lays off 60 DEI-related staffers... Five percent of Americans see the US as its own worst enemy, according to Gallup.

Trump Media & Technology Group sees Elon Musk's X as an option for those who want the free expression promised by Truth Social but without Donald Trump, owner of 57.3 percent of TMTG... Chalk one up for "anti-woke warrior" governor Greg Abbott as University of Texas lays off 60 DEI-related staffers... Five percent of Americans see the US as its own worst enemy, according to Gallup.

Have a comment? Send it to

Have a comment? Send it to

No comments have been submitted for this story yet.