Most students today can’t distinguish native advertisements from news articles, fake news from actual news or content posted by partisan groups from content posted by unbiased sources, according to findings from a recent study conducted by Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education.

The study, which took a year-and-a-half to carry out, collected responses from more than 7,800 middle school, high school and college students in a dozen states.

|

Students were presented with dozens of tweets, ads, comments and articles and asked to evaluate the content and credibility of that content, and were further asked to verbalize their reasoning as each task was carried out.

Researchers discovered that while young digital natives spend hours on the Internet each day and can navigate their way around social networks with ease, they’re “easily duped” when it comes to differentiating fact from fiction.

The study suggests that many students can’t distinguish advertisements from news. Specifically, the study discovered that students had a hard time telling the difference between articles and native advertisements, or branded content that’s been made to resemble editorial content.

In one portion of the study, hundreds of middle school students were presented with the landing page of online current affairs publication Slate, and were asked to evaluate and identify the varying content contained on that page: articles, traditional ads and native ads.

While 75 percent of students were able to correctly identify traditional ads on the page, an alarming 80 percent erroneously believed that native ads were news stories, even though that content was clearly labeled “sponsored content.” Others even noted that this content was “sponsored,” but still presumed they were bona fide news articles.

The findings were even more dire when it came to students’ ability to analyze the credibility of claims made over the Internet without evidence.

|

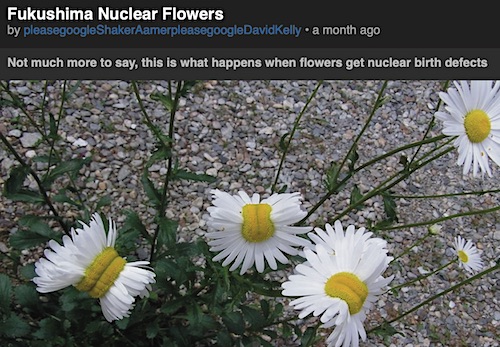

In another exercise, high school students were presented with an image from a popular photo-sharing site that claimed to show flowers growing near Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant that had “nuclear birth defects.”

Few students (less than 20 percent) questioned the source of the post or the photo’s veracity. On the other hand, 40 percent argued that the post provided sufficient evidence of its claims simply because it provided a photo. An additional 25 percent argued that the post didn’t provide strong evidence, but only because it showed flowers and not other plants or animals that may’ve been affected by the Fukushima disaster.

Finally, the study found most college students had a hard time detecting potential political bias in claims made over social media platforms.

College students were presented with a tweet regarding gun control posted by liberal advocacy group MoveOn.org, which linked to a poll sponsored by another liberal advocacy group, the Center for American Progress. Few students (less than a third) seemed able to recognize the potential political agenda working behind this post, even though students were allowed to click on the link as well as roam the web freely to research who these groups are.

Stanford researchers noted that while a great deal of variance is typically seen in studies that poll thousands of respondents, the subjects in their 18-month study displayed a “stunning and dismaying consistency” across each level of education, be it middle school, high school or college.

“Overall," researchers wrote, “young people’s ability to reason about the information on the Internet can be summed up with one word: bleak.”

“In every case and at every level, we were taken aback by students’ lack of preparation,” the study’s authors concluded. “Ordinary people once relied on publishers, editors, and subject matter experts to vet the information they consumed. But on the unregulated Internet, all bets are off… Never have we had so much information at our fingertips. Whether this bounty will make us smarter and better informed or more ignorant and narrow-minded will depend on our awareness of this problem and our educational response to it. At present, we worry that democracy is threatened by the ease at which disinformation about civic issues is allowed to spread and flourish.”

A look at today's magazines, newspapers and the graphics on television and consumer products raises the question of whether or not designers know their intended audience.

A look at today's magazines, newspapers and the graphics on television and consumer products raises the question of whether or not designers know their intended audience. PR and marketing departments are in the hot seat, as forecasts show that growth in advertising spend stalled in 2023 in the wake of cost-of-living increases and continued economic uncertainty.

PR and marketing departments are in the hot seat, as forecasts show that growth in advertising spend stalled in 2023 in the wake of cost-of-living increases and continued economic uncertainty. WPP has forged what it calls a “first-of-a-kind global agency partnership” with China’s TikTok, a short-form mobile video platform.

WPP has forged what it calls a “first-of-a-kind global agency partnership” with China’s TikTok, a short-form mobile video platform. Widespread disinformation may derail Biden/Harris agenda, according to a coalition of advocacy groups, who see the need for government-wide strategy to repair broken information ecosystem. (1 reader comment)

Widespread disinformation may derail Biden/Harris agenda, according to a coalition of advocacy groups, who see the need for government-wide strategy to repair broken information ecosystem. (1 reader comment) There's a media appetite for positive stories right now, anything to counterbalance the steady stream of bad news from the deadly spread of COVID-19. (1 reader comment)

There's a media appetite for positive stories right now, anything to counterbalance the steady stream of bad news from the deadly spread of COVID-19. (1 reader comment)

Have a comment? Send it to

Have a comment? Send it to

No comments have been submitted for this story yet.