Public trust in the U.S. government has been declining for several years. And the professionals who provide communications counsel for the government think the government itself is partially to blame, according to a national government and public affairs study on trust in government communications conducted by The Graduate School of Political Management at the George Washington University College of Professional Studies.

The national research project, which sought to examine the effectiveness of government and public affairs communications and the amount of perceived trust the public has in the government’s messaging capabilities, surveyed government communications practitioners as well as communicators employed by government-associated private sector organizations.

The study found that more than a third (35 percent) of the practitioners think the government is ineffective when it comes to public messaging, while nearly two-thirds (65 percent) characterized the government's communications capabilities as sufficient. Of all the respondents surveyed, 40 percent think the public distrusts the government’s messaging, while 59 percent believe the public trusts the information the government provides them.

What’s causing this perceived lack of trust in government messaging? A majority cited external factors: namely, the recent rise in fake news and disinformation, as well as a prevailing view that the government’s objectives are politically motivated. More than two-thirds (68 percent) believe disinformation is harming public trust in government, while 58 percent said the government is viewed as being politically motivated. Additionally, 59 percent think the recent hyperpolarization in politics, which can limit officials from being able to communicate fair and balanced information, is the reason for the current lack of trust in government.

But the government isn’t blameless in all this. In fact, the GW study suggests that the government’s current internal processes—which include needless bureaucracy, general disorganization, a history of withholding information and poor social media capabilities—have exacerbated its poor messaging performance, even if external factors are the root of the problem.

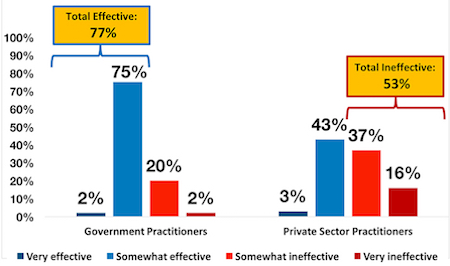

|

| Government communicators were asked: is the government’s messaging effective? Practitioners who work for the government were more likely to view the government as effective at communicating with the public, but private-sector practitioners with government clients were more likely to say the government’s PR approach is ineffective. |

More than a third (36 percent) of communicators polled said the government has a bureaucratic and outdated approach to communications, which often prevents government agencies and entities as well as government-associated private-sector organizations from getting information out quickly. And 31 percent think government communications are too monolithic and utilize a “one-size-fits-all” approach that doesn’t account for regional, demographic and/or socioeconomic differences, which hinders the government’s ability to communicate effectively.

More than a quarter (26 percent) of all communicators polled also said they think the government is too slow to share information, 23 percent believe the government’s approach is outdated and 19 percent said the government lacks the resources to effectively communicate. An additional 14 percent believe the government has lied or provided inaccurate information in the past, eight percent said the government hasn’t effectively mastered the use of social media, eight percent think the person delivering the message isn’t trustworthy and four percent said they find the government to be deceptive.

The study discovered a sizable disparity between the two groups surveyed in that communicators who are government employees widely see the government as being effective at communicating with the public (77 percent), while the majority of private-sector communicators working with government clients view the government as being ineffective (53 percent). And while most communicators surveyed admitted external factors such as the rise in disinformation are a primary contributor to the public’s lack of trust, government communicators are more likely to blame internal failures—such as slowness, an outdated approach and a lack of resources—for contributing to this phenomenon, while private-sector practitioners are more likely to cite public trust factors.

For example, 29 percent of government practitioners think the government is too slow to share information (compared to 22 percent of private-sector communicators), 28 percent think the government’s comms. approach is outdated (versus 15 percent of private-sector employees) and 28 percent believe the government currently lacks the resources to effectively communicate (compared to only seven percent of private-sector employees).

On the other hand, 21 percent of private-sector employees believe the government has deliberately withheld information in the past (versus 17 percent of government employees) and 24 of private-sector employees think the government has lied or provided inaccurate information (compared to only seven percent of government employees). A third (33 percent) of private-sector communicators blame the government’s “one-size-fits-all” comms. approach (compared to only 30 percent of government practitioners).

So, what steps can the U.S. government take to narrow the trust gap and improve outreach with its messaging? Practitioners suggested that government communications can be improved by ditching the monolithic approach, empowering communicators by bolstering education and training programs and examining their own internal processes so it can weed out disorganization, inefficiency and bureaucracy.

More than half (55 percent) of respondents suggested the government should refine its communications strategies and tactics to more effectively reach different groups of Americans. 51 percent said the government should either devote more resources and training for current staff or share information with the public quickly and more regularly. 47 percent highlighted the need to take a stronger stance against disinformation, 33 percent believe undertaking reforms to enhance bipartisanship would improve trust and 26 percent advocate eliminating bureaucratic challenges. Only 13 percent suggested improving the government’s social media usage and presence.

According to the study, communications pros believe written communications (71 percent) and interpersonal communications (57 percent) are the two most important skill sets for communicators to possess. 21 percent cited a deep knowledge of government policy and 10 percent said social media ability is the top skill to possess. Only six percent think a deep knowledge of politics is the most important skill set for government communications.

GW’s “Government Communications and Public Affairs Study” surveyed more than 200 communications professionals employed by the Federal, state and local government or government-affiliated private-sector organizations in November and December. Respondents were contacted using email lists provided by the National Association of Government Communicators, Ragan Communications, and GW/GSPM Students & Alumni. Research was conducted by Schoen Cooperman Research.

Husch Blackwell Strategies has added FleishmanHillard alum Michael Slatin as a principal in its public affairs group.

Husch Blackwell Strategies has added FleishmanHillard alum Michael Slatin as a principal in its public affairs group. Rory Cooper, a veteran Republican operative and policy specialist, has joined Teneo’s Washington office as senior managing director in its strategy & communications practice.

Rory Cooper, a veteran Republican operative and policy specialist, has joined Teneo’s Washington office as senior managing director in its strategy & communications practice. Brian Fallon, who served as national press secretary for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential run, is signing on next month as Vice President’s Kamala Harris’ campaign communications director.

Brian Fallon, who served as national press secretary for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential run, is signing on next month as Vice President’s Kamala Harris’ campaign communications director. TikTok is nothing more than a Chinese propaganda tool that poses “a grave threat to America’s national security and, in particular, impressionable children and young adults,” say two Congressmen who want the platform registered as a foreign agent.

TikTok is nothing more than a Chinese propaganda tool that poses “a grave threat to America’s national security and, in particular, impressionable children and young adults,” say two Congressmen who want the platform registered as a foreign agent. Public Strategies Washington has added Abbie Sorrendino, a former aide to now Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer.

Public Strategies Washington has added Abbie Sorrendino, a former aide to now Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer.

Have a comment? Send it to

Have a comment? Send it to

No comments have been submitted for this story yet.