“The Big Short,” a film on the 2008 financial meltdown that affected millions, skewers banks, Wall Street itself, the Fed, rating services such as Standard & Poors, and media such as the Wall Street Journal that failed to out the villains.

“The Big Short,” a film on the 2008 financial meltdown that affected millions, skewers banks, Wall Street itself, the Fed, rating services such as Standard & Poors, and media such as the Wall Street Journal that failed to out the villains.

Based on the 2010 book by Michael Lewis, who wrote "J-School Ate My Brain," a 1993 takedown of the Columbia J School, The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine, it attacks a complicated subject via lengthy explanations and comparisons, one of which is gamblers playing blackjack.

Non-players bet on those playing and others bet on them, multiplying the amount of money at risk. A “short sale” is selling stock or bonds you don’t own with the hope of buying them back or “covering” at a lower price.

Lewis has authored an extensive piece on the movie for the "Holiday" issue of Vanity Fair. He noted that Citigroup lost more than $65 billion and Merrill Lynch more than $50 billion. He acknowledges the difficulty of explaining collateralized debt obligations and credit-default swaps to the layperson.

He sees his job as making the reader want to know about these topics.

Only One Trader to Jail

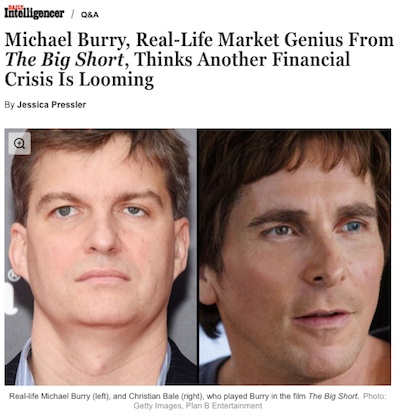

Michael Burry, the Wall Streeter portrayed by Christian Bale, told the Dec. 28 New York mag that he was “shocked” that only one of the traders involved went to jail. “Some of the worst lenders were not punished for what they did,” he told Jessica Pressler. Many lost their homes and even their lives “but the executives at the lenders simply got rich,” he said.

A Standard & Poor’s executive is shown saying that if S&P did not give good ratings to sub-standard investments someone else would. A WSJ editor is shown rebuffing pleas by Burry and others to expose excessive real estate speculation.

Anyone with a Pulse Got a Mortgage

Anyone with a Pulse Got a Mortgage

Banks were shown giving mortgages to people of limited income who made down payments as low as one percent of the market value. Home prices appeared to be skyrocketing with no end in site. Wall Street then started selling mortgage-backed securities based on the rising home prices. Buyers took “variable rate” mortgages that were a couple of percentage points. But when rates escalated, they were “squeezed” and couldn’t meet the payments. Millions defaulted on their loans.

This writer lived on Hearthstone drive in Greenwich where homes that initially sold for $50K in the 1960s rose as high as $2.2 million before 2008 only to crash to below $1 million. The scene was duplicated across the U.S.

Homeowners who wanted to pay off a mortgage were told to take a “home equity” loan instead at very low rates and tap into the wealth trapped in the value of their homes. Several years later, the rates went up to six and seven percent, doubling payments. Homeowners with enough income were able to switch to conventional mortgages at six percent and more. Others lost their homes.

Fed’s Policies Worsen Income Gap

Burry told New York that the Federal Reserve’s zero interest policy robbed the retired of needed income. With home prices beyond reach and bank interest near zero, investors were forced into the stock market if they hoped to “make money on their money.” This is one of the forces propelling the stock market.

Burry feels the economic system is under “terrific stresses” as the Fed tries to stimulate growth through easy money. Fed policies “widen the wealth gap which feeds extremism,” he says.

There’s a fine line between newsjacking and taking advantage, aka ambulance chasing. Our job as PR professionals is to tread it carefully.

There’s a fine line between newsjacking and taking advantage, aka ambulance chasing. Our job as PR professionals is to tread it carefully. PR firms need to be mindful of ways their work product may be protected by the attorney-client privilege whenever working with a client’s internal legal team or its external legal counsel.

PR firms need to be mindful of ways their work product may be protected by the attorney-client privilege whenever working with a client’s internal legal team or its external legal counsel. Manuel Rocha, former US ambassador and intenational business advisor to LLYC, plans to plead guilty to charges that he was a secret agent for Cuba.

Manuel Rocha, former US ambassador and intenational business advisor to LLYC, plans to plead guilty to charges that he was a secret agent for Cuba. CEO mentoring is an often-overlooked aspect of why CEOs are able to make good decisions, and sometimes make bad ones—all of which intersects with the role and duties of a board.

CEO mentoring is an often-overlooked aspect of why CEOs are able to make good decisions, and sometimes make bad ones—all of which intersects with the role and duties of a board.  How organizations can anticipate, prepare and respond to crises in an increasingly complex world where a convergent landscape of global challenges, threats and risks seem to arrive at an unrelenting pace.

How organizations can anticipate, prepare and respond to crises in an increasingly complex world where a convergent landscape of global challenges, threats and risks seem to arrive at an unrelenting pace.

Have a comment? Send it to

Have a comment? Send it to

No comments have been submitted for this story yet.